An ageing woman is found selling tissue packets on the streets without a permit. From a policy perspective, this could be approached either as a criminal matter of illegal hawking or an issue of social welfare. This elderly lady would certainly prefer the latter, as making her a criminal only aggravates her dire situation.

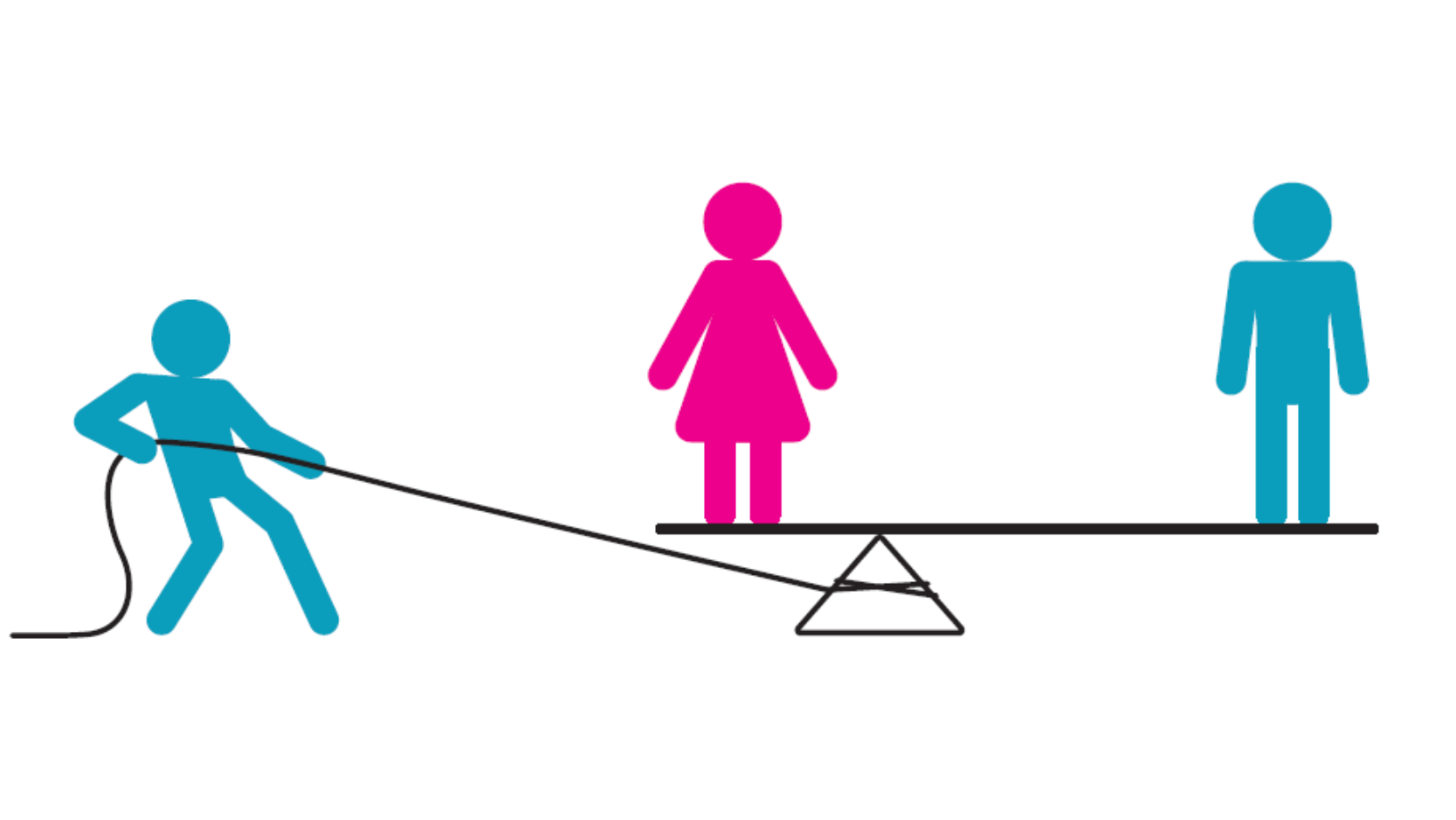

Framing matters. The frames that we adopt govern how we understand social issues and how we respond to them. In Singapore, there is a prevalent tendency to use ethnic frames in order to understand certain social issues. This is problematic. It prevents us from having a robust discussion about policy and structural issues, as it instead pushes us towards spurious culturalist accounts to explain away any social problem as a failing of that specific ethnic group.

CONSTRUCTION OF HEALTH AS A ‘MALAY’ PROBLEM

One example is that of the construction of health issues as a ‘Malay’ problem. A passage from a Straits Times article succinctly frames the problem: ‘Malays are too fat, getting fatter too fast and succumbing to chronic diseases in the process’.1 This is evidenced by statistical data in which over one in two Malays are too heavy, with a BMI of 25 or more, and one in five have a BMI of 30 and above. This is associated with high rates of obesity-related disease, such as diabetes and blood pressure.

Health surveys play a crucial role in the construction of obesity as a ‘Malay problem’. The 2010 National Health Survey2 highlights several traits of the Malay community. The breakdown of data across ethnic lines reveals that Malays have the highest blood cholesterol (22.6%) and obesity levels (24%). Framed in this manner, the statistics depict a grim view of the health conditions of the Malay community.

Such a framing feeds into the tendency to seek culturalist explanations for the obesity crisis. In an article in the Berita Harian, a male journalist argued that Malay women were now more likely to be obese due to their tendency to over-eat while doing little work – a stark contrast to the past where women were kept busy with housework.3 Here, again, it is the contemporary cultural norms of the Malay community that is blamed for engendering obesity.

The selection of ethnic frames as the dominant mode of breaking down health data, which comes attendant with spurious culturalist explanations from this ‘Malay problem’, presents a missed opportunity for a more nuanced discussion of health and obesity.

For instance, the book The Spirit Level4 argues for the role of socio-economic class as a causal factor for obesity. According to the analysis, although the effects of modern living have contributed to increasing rates of obesity, not all developed countries suffer uniformly from obesity: countries like the United Kingdom and the United States may suffer from high rates of obesity, but this is not true of many other modern states such as Japan and Sweden. The authors thus argue that economic inequality is a variable that affects the level of social dysfunctionality within a country. Socio-economic class is very much linked to obesity as people with lower incomes and social standing are more likely to consume ‘energy dense’ foods which are often cheaper and more accessible. The poor usually neither have the time nor finances to make health-conscious food choices. Another aspect of class which directly affects health and obesity is work. Stress resulting from poor working conditions or precarious employment conditions can adversely affect health. Hence, class and income should be salient to any discussion of health and obesity – such data was however notably absent in the National Health Survey.

Other factors which can affect health and obesity rates that should be taken into consideration are urbanisation, the growth and prevalence of the fast food industry, as well as a consumerist culture that encourages consumption of processed foods. Having more of such metrics and data would allow a more informed and nuanced engagement with our health policy – instead, the demographic breakdown of the National Health Survey leaves us with the framing and racialising of obesity as a ‘Malay problem’.

BETTER DATA, MEDIA COVERAGE NEEDED

Frames thus matter. Framing issues through an ethnic lens not only reproduces and reinforces futile and inaccurate cultural stereotypes, but it also prevents us from having a constructive discussion about policy shortcomings stemming from the social structure and built environment. The challenge now is to transcend these ethnic frames and instead engage these issues at a deeper and more nuanced level.

It might help, for one, if more raw data can be collected and made available to all. Statistical data that is presented to the public must be more varied and comprehensive. The construction of obesity as a ‘Malay problem’ attests to this. By releasing only one set of statistical data (i.e. data grouped by ethnic sets), it gives a veneer of objectivity to claims arising from the cultural deficit thesis. The collection and publication of more data points will allow policymakers, academics, and civic-conscious citizens an opportunity to re-interpret and re-think the social issues from a different perspective. Instead of along ethnic lines, presenting such data on health in terms of income will introduce a fresh dimension to our understandings as we seek to find new correlations and patterns of behavior and consumption.

Secondly, the role of the media is crucial. The media has a responsibility to critically interrogate such ethnic framings, instead of blindly perpetuating such narratives. This is not a simplistic endorsement of anything and everything alternative: what is necessary is that such perspectives are questioning dogmas and assumptions rather than merely perpetuating myths and stereotypes.

Ethnic frames, while convenient, are inadequate in understanding complex social issues. This is not to say that data presented across ethnic lines are not relevant – it might be. In certain cases, having ethnic data may make policy implementation and outreach more effective. However, while data presented across ethnic lines might be relevant, it is definitely not sufficient. At this stage, political and policy discourse in Singapore can only mature if we avoid relying on ethnic frames as a crutch to interpret and diagnose social problems. ⬛

1 Chang Ai Lien ‘Malays and Obesity: Big trouble’ Straits Times, 13 Mar 2010.

2 National Health Survey 2010 Epidemiology and Disease Control Division, Ministry of Health.

3 Mengapa Wanita Melayu Kini Gemuk-Gemuk?’ Istimewa, Berita Harian, 27 Mar 2011.

4 Wilkinson, Richard and Pickett, Kat e (2009) The Spirit Level: Why More Equal Societies Almost Always Do Better Allen Lane

Muhammad Fadli Mohd Fawzi is currently working as associate faculty at Singapore Institute of Management while doing his Juris Doctor at Singapore Management University. He has a wide range of interests which include issues of socio economic justice, sustainable economic development and alternative historical narratives.