The progress of the Malay community has been a concern among national and Malay leaders since Singapore declared independence in 1965. National statistics show the Malays are lagging in areas such as education and income when compared to other communities. The gaps persisted even over the last 30 years despite key developments such as the establishment self-help group, MENDAKI (refer to Charts 1, 2 and 3). What, however, has not remained as consistent is the narrative of the Malay progress. This has changed over time.

From the 1970s till around the 2010s, leaders had been making statements which imply that either the sociocultural or attitudinal factors prevalent among the Malays have had a part to play in perpetuating the lag.

Former Parliamentary Secretary for Culture, Sha’ari Tadin, said in 1970 that it was cultural education which made the Malays contented and obedient, thus resulting in the Malays not having an inquisitive mind. He described it as the “wrong kind of education”.1

At the MENDAKI Congress on education held in May 1982, then-Minister-in-charge of Muslim Affairs, Dr Ahmad Mattar, cautioned that whatever MENDAKI and its intellectuals and activists did will not be able to replace attitudes necessary for every family, individual and student to uplift educational attainment.

Similarly, in a seminar on Education and Singapore Malay Society: Prospects and Challenges held by the Malay Studies Department, National University of Singapore in January 1991, former Senior Minister of State, Mr Sidek Saniff, stressed the need to broaden and intensify efforts to change the attitude and educate parents, especially those from the lower socioeconomic group.

The call for a change in attitudes stems mainly from the tendency to compare the Malays with other communities.

In the 1982 MENDAKI Congress, former Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew said that “…the importance of performance in examinations has become part of the culture of Chinese. The Indians too are keenly aware of the importance of studies and examinations as the road to success…” which implicitly suggested that the Malays have yet to acquire such values2. Mr Sidek also mentioned that “…the Malays as a group are still lagging behind the other ethnic groups in academic achievement” in the 1991 seminar.

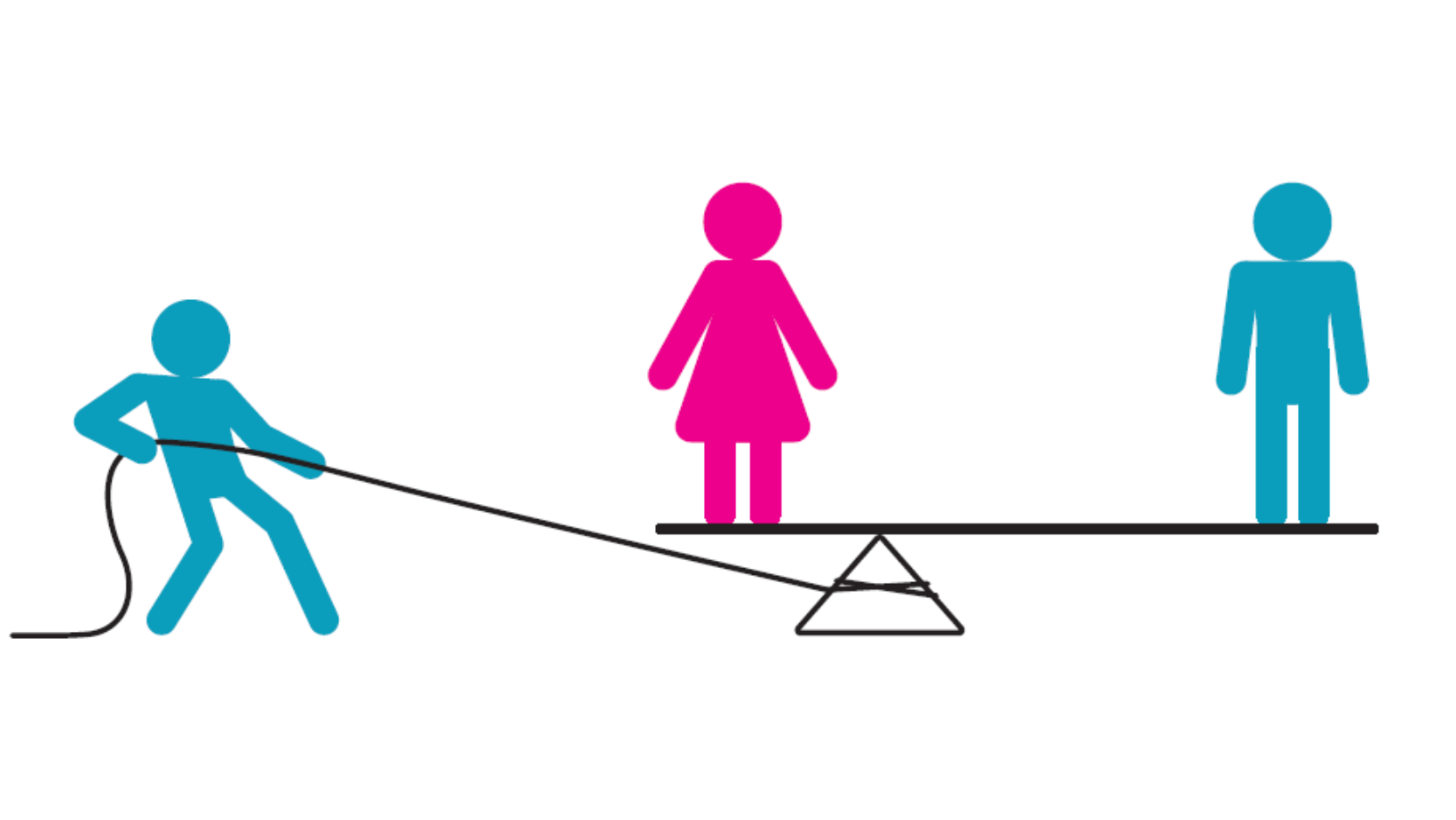

ABSOLUTE VS RELATIVE PROGRESS

However, the stance adopted by present day leaders showed a noticeable shift from that of their predecessors. During a Hari Raya Get-Together event on 8 August 2013, the current Minister-in- charge of Muslim Affairs, Dr Yaacob Ibrahim, said, “Over the years, our Malay/Muslim community has made considerable progress in our quest to scale many peaks of excellence. Rising educational achievements brought us higher income and wealth.”

On his appointment to the Cabinet as the second Malay minister, Mr Masagos Zulkifli, said, “It is good to see more and more Malays doing very well in education, doing very well in all fields of their professions and even in Government, and I’m very happy for that.”

The change in the Malay leaders’ articulation of the community’s progress seems to follow from what Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong said in his speech during the Third National Convention of Singapore Muslim Professionals held in 2012. While acknowledging that the gaps should not be ignored, he had urged the community not to focus on comparing themselves with other communities. Doing so would be akin to benchmarking against “a moving target”, as other communities could either be doing better or worse. Instead, he had suggested measuring progress from the Malays’ own “starting point”.

Considering what Mr Lee had said, the Malays are now perceived to have been doing well despite the earlier portrayals by the leaders. The reason is that there has been absolute progress (depicted by the rising curves of the Malays in Charts 1 to 4) as opposed to a relative one vis-à-vis the other communities which show the disparities prevailing, widening in some cases as they approach recent years (Charts 1 and 3). Absolute progress has been taking place over the last 30 years, as corroborated by Mr Lee in his speech during MENDAKI’s 30th anniversary dinner in 2012 when he said, “The community’s education performance has improved significantly in these last 30 years. It does not matter which indicator you look, there has been progress.”

As Singapore prepares to celebrate its 50th National Day, perhaps the time is right to revisit the narrative on the Malay community’s progress.

REVISITING THE “MALAY PROGRESS” NARRATIVE

Firstly, the complexity of analysing the dominant attributes of the community must be acknowledged. As is the case with most communities, the Malays are culturally and socioeconomically diverse. Contrary to perception of Malays being clumped into one lower socioeconomic group, they are in fact spread across the income strata, indicating a class divide within the community. Accordingly, the expectations, value systems, behaviours and responses to policies and other developments of one Malay group differ from another. Given this, and the cultural diversity of the Malay community, statements to the tune of Malays needing a mindset change, as articulated by some leaders, may not achieve any meaningful outcome.

Secondly, there is a need to review the ways in which national statistics, such as the Ministry of Education’s annually released “10-Year Trend of Educational Performance” report – which provide the breakdown of data by ethnicity – are being used to explain the Malay progress.

To date, the discourse on the progress of the Malay community has been centred mainly on the idea of self-help, thus playing down the significance of national factors in the Malay community’s development trajectory. To credit the former with the community’s progress, it has to be ascertained that the participation of Malays in the community’s self-help initiatives has reached a critical mass, which is essentially the minimum number needed to influence national level statistics. Otherwise, it would be misleading to use such data to evaluate the community’s efforts.

To illustrate this point, we can examine the oft-cited case of students advancing to post-secondary institutions between 1990 and 2013. The rising trend is observed across communities, not just the Malay community (The curves are understandably flatter as they approach the 100-percent mark). It hints that a number of factors were at play.

During this period, there were changes to education, economic and social policies and circumstances. To claim that self help initiatives have a more profound role than these factors in influencing the community’s statistics requires substantiation that has hitherto not been produced.

Moreover, according to a study commissioned by MENDAKI, about two-thirds of low-income Malay/Muslim households do not seek help from social services despite hopes that their children can escape the poverty trap. It begs the question: what is the take-up rate of the community’s self-help programmes?

Moving on, a pertinent question that needs to be asked now is whether it is time for the emerging national narrative on success to take precedence over the community’s narrative of progress.

The SkillsFuture initiative announced by Deputy Prime Minister Tharman Shanmugaratnam in his Budget 2015 speech is a national movement that will give impetus to redefining success. According to the SkillsFuture website, it aims to provide Singaporeans with opportunities to develop their fullest potential throughout life, regardless of their starting points. Hence, it is set to challenge established norms of couching success in terms of standardised test performance and the eventuality of landing jobs in ‘prestigious’ disciplines like medicine and law.

The next phase of development towards an advanced economy and inclusive society could see greater recognition being accorded to the many other forms of intelligences that are vital at both the micro and macro levels: the individual’s ability to satisfy future job requirements that are poised to place greater emphasis on talent and skills than mere academic qualifications; and forging a more innovative and creative culture in order for Singapore’s economy to maintain its comparative advantage in terms of human capital over developing economies that are fast catching up.

Going forward, will the community’s narrative on progress continue to be framed along ethnic and sociocultural lines, with other communities seen as if they are control groups? Will there be acknowledgement that national factors have a profound impact on the community’s progress? Will the new narrative embrace a broader definition of success and acknowledge that the Malays have the wherewithal and acumen to seize the opportunities that are right for them? It will be interesting to see how the “Malay progress” narrative changes as Singapore advances beyond its 50th year of independence. ⬛

1 This was mentioned in his speech at a seminar organised by the Central Council of Malay Cultural Organisations and the Community Study Centre on Friday, 11th December 1970.

2 This view is expressed by Dr Suriani Suratman in her paper entitled, “Problematic Singapore Malays” – The Making of a Portrayal.

Abdul Shariff Aboo Kassim is a Researcher / Projects Coordinator with the Centre for Research on Islamic and Malay Affairs (RIMA), the research subsidiary of the Association of Muslim Professionals (AMP).