THE CHANGING LANDSCAPE

Today’s young people are the most educated generation ever. They often enter the working world with considerably more years of schooling than their parents or grandparents. In Singapore today, more than 95 percent of each cohort of students progress to post-secondary education as compared to only 22 percent of those born in the 1940s[1].

However, the overall increase in education standards also means youth today face a new set of challenges and greater pressure to remain competitive and employable. There are greater expectations to do well academically and it is even more difficult for one to stand out amongst a sea of graduating students. Moreover, the influx of foreign talent in recent years has raised the bar for many job seekers, making it more competitive in finding or sustaining jobs[2].

In addition, globalisation and technological advancements are disrupting jobs and industries that were once assumed safe and stable. The accelerating pace of technological advancements and socio-economic disruptions are altering industries and business models on a significant scale. Most notably, such disruptions saw the transformation of skills in demand and decrease in the shelf-life of current skill sets. In banks for example, technology can now do a huge part of what analysts do, such as carrying out online research, analysing and crunching data, and organising charts and graphs.

Singapore’s youths are now growing up in a different world, characterised by unprecedented changes fuelled by the proliferation of technology and digital innovation, which has significantly altered the nature of work. The rise of the gig economy, for instance, which is powered by the proliferation of smartphones and the Internet, has birthed an entirely new category of employment that continues to grow in depth and breadth. Gig workers can independently seek employment on an ad hoc basis, without being confined within the structures of a company or organisation. A growing proportion of Singapore’s workforce, including the young graduates, is now gravitating towards freelance jobs offered by the gig economy.

Against this backdrop, it is critical for us to ensure that Malay/Muslim youths are positioned to navigate this disruption and remain relevant in the employment landscape.

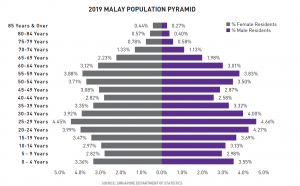

YOUTH BULGE IN THE MALAY POPULATION

If we look at the 2019 population pyramid of the Malay community, you would notice that it has a very youthful population structure. Social scientists label this demographic profile the youth bulge, which is defined as young people making up the highest proportion of the population.

Being born into a large youth cohort usually means heightened competition and fewer employment opportunities. With a younger age profile than the general population, the share of employment of Malay youths is expected to increase. A youthful population structure is a demographic edge and advantage – but only if these young people are being employed in decent jobs.

Former World Bank Chief Economist Justin Yifu Lin, explains that the conventional approach to managing a youth bulge is to make young people job-ready through investment in human capital to enhance productivity in the labour market[3]. Hence, recognising this demographic trend and effectively addressing the needs of youth are pivotal for the future.

CONSTRAINTS TO YOUTH EMPLOYMENT

The Centre for Research on Islamic and Malay Affairs (RIMA) conducted a qualitative perception study to understand the nature of barriers to employment faced by Malay/Muslim youths. The study, titled Voices of Youth: A Conversation on Employment, also briefly reviews the demographic situation in the Malay/ Muslim community and its impact on employment. In addition, the study addresses how Malay/Muslim organisations (MMOs) can play a key role in combatting the problems and providing solutions.

In the youth perception study, participants shared common key employment concerns such as battling with mismatched jobs, low salary, poor working conditions, unfavourable treatments and relations at work, and a lack of community support.

According to the qualitative study, youth participants are broadly concerned that there are few opportunities for decent work. The clear message among many of the study participants is that when they do obtain jobs, it involves poor wages as well as poor working conditions, including heavy workload, long hours, having few or no prospects for advancement, and a lack of benefits. Youth participants found themselves crowded out in the job market and the type of jobs they wanted, and having to accept a lower-paying job, which may mean a lower likelihood of them moving on to a better job in the future.

Moreover, certain segments of the youth population see their prospects limited by additional constraints. For instance, majority of participants with a Higher Nitec qualification or below highlighted that it is hard to get a response from employers in their job search, unless their salary expectation is lowered because of their academic qualification.

For youths with a higher educational attainment, academic success alone has proven to be an insufficient means of ensuring a smooth transition into decent employment. For participants with at least a diploma qualification, inadequate skills and mismatch between education and skills have emerged as chief concerns. Majority of them from this group shared sentiments where their educational plans are out of kilter with their job expectations. These participants shared about not receiving sufficient employment information and career guidance which sometimes led to ill-informed career choices or unnecessarily long periods of job search after graduation.

In a survey conducted by the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy and Ong Teng Cheong Labour Leadership Institute in 2017, about 4.31 percent of the respondents were severely unemployed. These were degree holders earning less than $2,000 a month despite holding full-time jobs[4]. In another survey, findings suggest that about one in four fresh graduates from private education institutes were either unemployed and still looking for a job, or in involuntary part-time or temporary employment[5].

An interesting point discovered in the RIMA study is the attitude towards employment among the group of respondents. For instance, participants with a Higher Nitec qualification or below shared that they would rather be active than “sit around” and be unemployed. Meanwhile, participants with at least a diploma qualification and above shared that they prefer to remain unemployed than accept what they consider undesirable jobs which most of them defined as having a “lousy” pay or heavy workload.

The youth study also found that most of the participants did not have any network of contacts or referrals when looking for jobs. For majority of them, their network constitutes mainly people of similar occupational, educational and income background. This left them with limited resources at their disposal, and hence, insufficient information on available decent jobs.

The data from the study also shed light on the lack of awareness among the youth participants about the opportunities that are available in Singapore’s labour market. For instance, when asked about the existence of job assistance platforms, majority shared that they had heard about the schemes or at least had come across services of these platforms nor did they explore opportunities when they encountered difficulties in looking for jobs. They cited the complexity of the system when asked about the reason for not doing so.

Most of the participants also asserted that the more common experience they had was witnessing discriminatory behaviour among hirers, employers, colleagues or clients. Such episodes include managers being critical of them while lenient to others. Participants shared instances where they perceived hirers and employers being discriminative towards them, making their employment experience difficult.

Similar sentiments were shared in the findings of a survey conducted by the Institute of Policy Studies and OnePeople.sg on racial and religious harmony. Almost 60 percent of Malay/Muslim respondents perceived discriminatory treatment at work; a slight increase from the 58.7 percent in their previous study[6]. Minority groups also reported that they felt discriminated against when applying for jobs or seeking a promotion.

When asked, majority of the youth participants expressed hope that MMOs can do more to help them in areas such as career guidance and counselling. Indeed, with young people staying in education longer than ever and facing increasingly difficult decisions about how to prepare for the labour market, it is more important than ever to get career guidance right. In addition, participants also shared that they hope MMOs can provide youth-friendly, tailored job-matching services, advice on actions to take when employers or colleagues are discriminative, organise resume writing and interview training for job seekers, as well as introduce top-up schemes for individuals who are keen to sign up for courses but cannot afford the fees despite government subsidies.

BRIDGE TO BETTER EMPLOYMENT OPPORTUNITIES

It is important to recognise that all young people will experience a variety of employment issues at some point in their lives, which will lead to different future outcomes. Not everyone will enjoy the same opportunities to develop their academic ability and personal skills or rise through the ranks to secure a more senior position, which commensurates with remuneration.

According to the RIMA youth perception study, while younger workers may face disadvantages in the labour market, some are more vulnerable to poor employment prospects. They include at-risk cohorts such as youths with lower academic qualifications, as their career is more likely to experience stagnancy or even a downward trajectory. Hence, support for at-risk youths, given the likely challenges they will face in the job market, is critical to improve their chances of employment. Ideally, support should begin even while our youths are in school.

Strengthening a youth’s ability to take advantage of job opportunities starts with ensuring they are equipped with the relevant skills for emerging industries. Most of the youths that were interviewed in the study started work early in their lives and hence, lost out on the opportunity to be adequately trained. Empowering them to be trained requires enhancing access to network and information.

Ensuring that our youth is equipped with the right skills to complete their schooling, access further education or training, or gain employment is critical to a successful school-to-work transition. For all young people to successfully navigate this process and meet the inevitable challenges they face as they mature is critical. Young people need to nurture their aspirations. Coupled with foundational employability skills and career exposure, this will place all young people in a healthy position for a productive future.

In preparing the workforce for the future, it is important that young workers get a good start in their careers with suitable workplace conditions, and the recognition of the inter-relational dynamics between their education, age, culture, and the nature of the job market. Despite the best of intentions and measures in place, there are ways a young person can still fall through the cracks. The community needs to have continuous dialogues and conversations with youths. This means pointing them in the right direction as much as showing them the options, where available. Much remains to be done to support a young person in their personal and capability development for the job market. Efforts in this area should continue towards ensuring that our youth maximise their economic potential.

The youth bulge in the Malay population structure constitutes potential. If a large youth cohort is unable to find employment, the youth bulge will become a demographic bomb. However, if we can ensure that youths are put to work as productive citizens, the youth bulge can be a demographic dividend. ⬛

1 PRIME MINISTER’S OFFICE SINGAPORE. SPEECH BY DEPUTY PRIME MINISTER AND MINISTER FOR FINANCE HENG SWEE KEAT AT THE SINGAPORE YOUTH AWARD 2019 PRESENTATION CEREMONY ON 3 NOVEMBER 2019. RETRIEVED FROM HTTPS://WWW.PMO.GOV.SG/NEWSROOM/DPM-HENG-SWEE-KEAT-AT-THE-SINGAPORE-YOUTH-AWARD-2019-PRESENTATION-CEREMONY

2 PANG, E. F., AND DE MEYER, A. WITHIN & WITHOUT: SINGAPORE IN THE WORLD; THE WORLD IN SINGAPORE. SINGAPORE MANAGEMENT UNIVERSITY, 2015. RETRIEVED FROM HTTPS://INK.LIBRARY.SMU.EDU.SG/CGI/VIEWCONTENT.CGI?ARTICLE=6604&CONTEXT=LKCSB_RESEARCH

3 LIN, J. Y. YOUTH BULGE: A DEMOGRAPHIC DIVIDEND OR A DEMOGRAPHIC BOMB IN DEVELOPING COUNTRIES? WORLD BANK. 2012, JANUARY 5. RETRIEVED FROM HTTPS://BLOGS.WORLDBANK.ORG/DEVELOPMENTTALK/YOUTH-BULGE-ADEMOGRAPHIC-DIVIDEND-OR-A-DEMOGRAPHIC-BOMB-INDEVELOPING-COUNTRIES

4 CHENG, K. SURVEY FINDINGS ON UNDEREMPLOYMENT SHOW S’PORE’S ‘GRADUATE POOR’ EARN LESS THAN $2,000 A MONTH. TODAY. 2018, APRIL 10. RETRIEVED FROM HTTPS://WWW.TODAYONLINE.COM/SINGAPORE/SURVEY-FINDINGS-UNDEREMPLOYMENT-SHOW-SPORES-GRADUATE-POOR-EARN-LESS-2000-MONTH

5 TANG, L. 1 IN 4 PRIVATE SCHOOL GRADS UNEMPLOYED, INVOLUNTARILY WORKING PART-TIME 6 MONTHS AFTER GRADUATION. TODAY. 2019, APRIL 10. RETRIEVED FROM HTTPS://WWW.TODAYONLINE.COM/SINGAPORE/1-4-PRIVATE-SCHOOL-GRADS-UNEMPLOYED-INVOLUNTARILY-WORKING-PART-TIME-6-MONTHS-AFTER

6 LIM, A. RACIAL, RELIGIOUS HARMONY IN S’PORE IMPROVING, BUT MINORITY GROUPS FEEL DISCRIMINATED AT WORK: IPS-ONEPEOPLE.SG SURVEY. THE STRAITS TIMES. 2019, 30 JULY. RETRIEVED FROM HTTPS://WWW.STRAITSTIMES.COM/POLITICS/RACIAL-RELIGIOUS-HARMONY-IN-SPORE-IMPROVING-BUT-MINORITY-GROUPS-FEEL-DISCRIMINATED-AT-WORK

Nabilah Mohammad is a Senor Research Analyst at the Centre for Research on Islamic and Malay Affairs (RIMA). She holds a Bachelor of Science in Psychology and a Specialist Diploma in Statistics and Data Mining.