In July 2021, the United Nations Children’s Fund and the United Nations Education, Scientific and Cultural Organization issued a joint press release calling for the reopening of schools across the world. The press release lamented the fact that over 156 million students were being adversely affected by the continuing closure of schools in 19 countries as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. Both organisations expressed concern that “the losses that children and young people will incur from not being in school may never be recouped”.

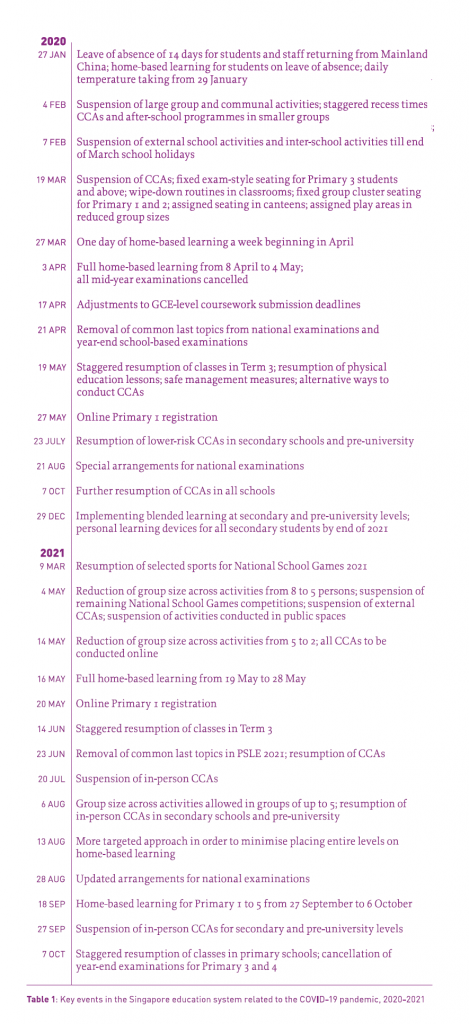

In Singapore, the pandemic has created tremendous disruption in all aspects of education too over the past two years. The key events are shown in Table 1. These range from total school closures to suspensions in co-curricular activities and reduction in the scope of content coverage for national examinations. This article will summarise and examine the effects of the pandemic on mainstream schools, and ask key questions about the purposes of education that many of us may not have given a second thought to. Key among the changes wrought by the pandemic are probably disruptions to classroom teaching and learning in all mainstream schools. When the first signs of COVID-19 began appearing in Singapore in January last year, the Ministry of Education (MOE) suggested home-based learning (HBL) be put in place for students who had been placed on leave of absence. By the end of March 2020, the MOE took tentative steps towards a wider implementation of HBL by announcing that it would be carried out in all schools one day each week beginning in April. This was followed a week later by the imposition of two months of HBL.

THE EFFECTS OF HOME-BASED LEARNING

Before the arrival of COVID-19, none of the mainstream schools would have experimented with HBL on such a sustained scale. Probably all teachers, students and parents were caught off-guard. Teachers soon realised the premium placed on their adaptability and ingenuity, as online lessons could not be conducted in a manner identical to that for face-to-face lessons. In addition, there were pre-existing concerns about the dangers of excessive screen time, especially in the case of younger students. How could teachers continue to capture their students’ attention and conduct group activities when the students were no longer in the same physical space with each other and with their teachers? And how about assessment of student learning, especially in the case of those students preparing for national examinations?

During HBL periods, schools have continued to remain open, in order to help students who lack conducive home environments, whose homes do not have access to Wifi, or whose parents are unable to provide adequate childcare arrangements. Some students also lack personal learning devices, a problem that the MOE attempted to alleviate through the loan of digital devices. Consequently, the MOE has accelerated its plans to provide every secondary student with a personal learning device. The periods of HBL in 2020 and 2021 have also placed increased responsibility on parents, especially in the case of primary school students, to help their children access online learning and stay focused during these lessons.

When announcing the imposition of HBL in March last year, the MOE acknowledged that “HBL will not be able to fully replace the depth and variety of learning experiences that our students derive from being physically present in school”. This point was exemplified clearly when graduating cohorts in mainstream schools were asked to return to school for extra lessons during the mid-year school breaks last year and this year, and when the MOE announced a reduction of curriculum coverage for the national examinations. These two policy measures have added urgency since Singapore has decided, unlike some other countries, to continue with staging these crucial examinations, instead of resorting to school-based assessments as an alternative means of assessment. Also, the MOE announced the need for ‘curriculum recovery’ (or the re-teaching of topics) when Primary 1 to 5 students returned to school for Term 4, and the cancellation of Primary 3 and 4 year-end examinations in 2021.

It is clear that HBL is far from adequate in the case of activities such as laboratory practical lessons and physical education classes. HBL is probably not the first choice either when it comes to helping students with special learning needs. Despite considerable advances in educational technology, face-to-face lessons in school are still likely to retain their dominant role, with online learning playing a supplementary role.

SCHOOLS: A PLACE FOR MORE THAN JUST ACADEMIC LEARNING

The MOE’s remarks about the inadequacies of HBL extend to the non-academic aspects of school life too. Over the past two years, non-academic activities, such as co-curricular activities (CCAs), inter-school competitions, learning journeys, overseas trips and inter-school competitions, have been severely curtailed. The MOE website claims that CCAs “play a key role in students’ holistic development”. Not only do CCAs enable students to discover their talents and interests, they also help students to learn values and social-emotional competencies and skills. Next, they provide a means for students from diverse backgrounds to mingle and develop friendships, while promoting a sense of belonging to school and the wider community.

The MOE’s repeated and sustained attempts to resume CCAs as much as possible bear testament to the importance it attaches to them. The curtailment of these activities, as well as the resulting consequences, reminds us that mainstream schooling involves far more than classroom teaching and learning. A great deal of the value of mainstream schooling lies in its socialisation function. In the case of some students from troubled homes or disadvantaged backgrounds, attending school also provides a safe environment and a source of adequate nutrition through school meal subsidies.

The prolonged nature of the pandemic has raised questions about student well-being, especially in the light of safe management measures within schools and in the wider community, and the substantial reduction in CCAs. In response to questions raised on this matter in Parliament, the MOE has recognised the possible detrimental effects on students’ socio-emotional development and mental well-being[1]. The Ministry has therefore announced plans for a more targeted approach towards ‘ring-fencing’ cases and their close contacts, rather than resorting to full HBL across all schools, or an entire level of students within a particular school.

At this stage, it is important not to ignore the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on teachers. The Minister for Education recently told Parliament that teachers’ workloads have doubled during the pandemic. First, teachers have had to prepare for online lessons and the possibility of HBL being imposed, while conducting ‘curriculum recovery’ after periods of HBL. Secondly, they have also had to address issues related to their students’ well-being, and in some cases, help their students’ parents adjust to the periodic disruptions too. Thirdly, teachers have also had to ensure their students adhere to safe management measures and undertake the arduous task of contact tracing.

In summary, the past two years have witnessed considerable disruption to the workings of mainstream schools in Singapore. In addition to changes in the way teaching and learning activities are conducted, the imposition of safe management measures have also had adverse effects on the non-academic aspects of school life. This article reminds us of the main purposes of mainstream schools, purposes that we used to take for granted prior to the sudden emergence of COVID-19. For one, the experiments with HBL have told us that while there is a role for blended learning, or the use of both online learning and traditional face-to-face teaching, we should think carefully about the centrality of face-to-face contact and exactly how online learning can supplement it. Secondly, schooling includes many non-academic experiences that cannot be replicated in an online setting. These experiences are a vital part of students’ overall development and it is regrettable that the pandemic has contributed towards their marginalisation. Thirdly, the past two years have helped foreground issues related to social and educational inequalities. Schools play a major role in helping students with special learning needs, and those from emotionally fragile or financially needy homes. As a final point, even while we consider the effects of the pandemic on students, due consideration needs to be given as well to teachers’ well-being. ⬛

1 Ministry of Education. Impact of HBL on students’ learning and development. 2021, October 4. Available at: https://www.moe.gov.sg/news/parliamentary-replies/20211004-impact-of-hbl-on-students-learning-and-development

Jason Tan is an Associate Professor in Policy, Curriculum and Leadership at the National Institute of Education, Singapore.