One observable phenomenon sweeping the world today is the increasing religiously-aligned tensions and conflicts, where Christians and Muslims emerged as the most frequent targets of abuse from groups or individuals for “acts perceived as offensive or threatening to the majority faith”. Christians were the subject of harassment in 102 out of the 198 countries studied by the Pew Research Centre in 2014, while Muslims were harassed in 99 countries. These harassments ranged from physical assaults to arrests and detentions, the desecration of holy sites, discrimination and even verbal assaults.

The irony is that both communities were often targeting each other, as much as they were themselves the subject of discrimination, intimidation, harassment or outright persecution. Christian minorities were targeted severely in several Muslim-majority countries where militancy is growing. In the European Islamophobia Report 2015, 25 European states were also found to have a worrying increase in hate-crimes against Muslim communities, particularly in France after the ‘Charlie Hebdo’ incident. America, too, had seen 10 states legislating bills deemed to be anti-Islam and the emergence of “Muslim-free businesses” and “armed anti-Islam demonstrations”, according to the Council of American-Islamic Relations (CAIR) in the same year. The deteriorating treatment of Muslims in Europe and America were often driven by Far Right movements, many of whom were White and Christian in membership; just like radical-extremist groups such as Hizb ut-Tahrir and the vigilante Islamic Defenders Front (FPI) in Indonesia are Muslim-based and employ Muslim rhetoric.

EXTREMISM AND ITS INTERSECTION WITH RELIGION, POLITICS AND ECONOMICS

There is also a correlation between the rise in religio-political extremism and the treatment of religious minorities. Christian minorities were often targeted by Muslim militants who perpetrated violence by way of retaliating against foreign military interventions. The rise of Donald Trump was built upon anti-Muslim rhetoric. Similarly in Europe, right-wing political parties, such as the Partij voor de Vrijheid in the Netherlands and the National Democratic Party in Germany, often stoked anti-Muslim sentiments in a bid to gain entry into parliament.

The rise in attacks on Muslims also coincides with anti-immigrant sentiments. Yale Law School professor, Dr Amy Chua in her book, World on Fire (2002) highlighted how the process of globalisation can be detrimental in societies with deep ethnic cleavages and imbalanced distribution of economic resources. In the case of Muslims in Europe, it is not the majority’s envy of the privileged minority; it is xenophobia coalescing with a long-standing problem of racism. While rapid migration and the lack of integration spell the problem for Muslim minorities in the West, it is also driven by a deep-seated fear of Islam – or what has been conceptualised as ‘Islamophobia’.

ISLAMOPHOBIA IN SINGAPORE?

Given the above, it is important to understand that Singapore is not immune to these challenges. Drawing a link between extremism and inter-religious tensions, Home Affairs and Law Minister, K Shanmugam raised the possibility of Islamophobia taking root in Singapore society along with the phenomenon of religious extremism in Muslim societies.

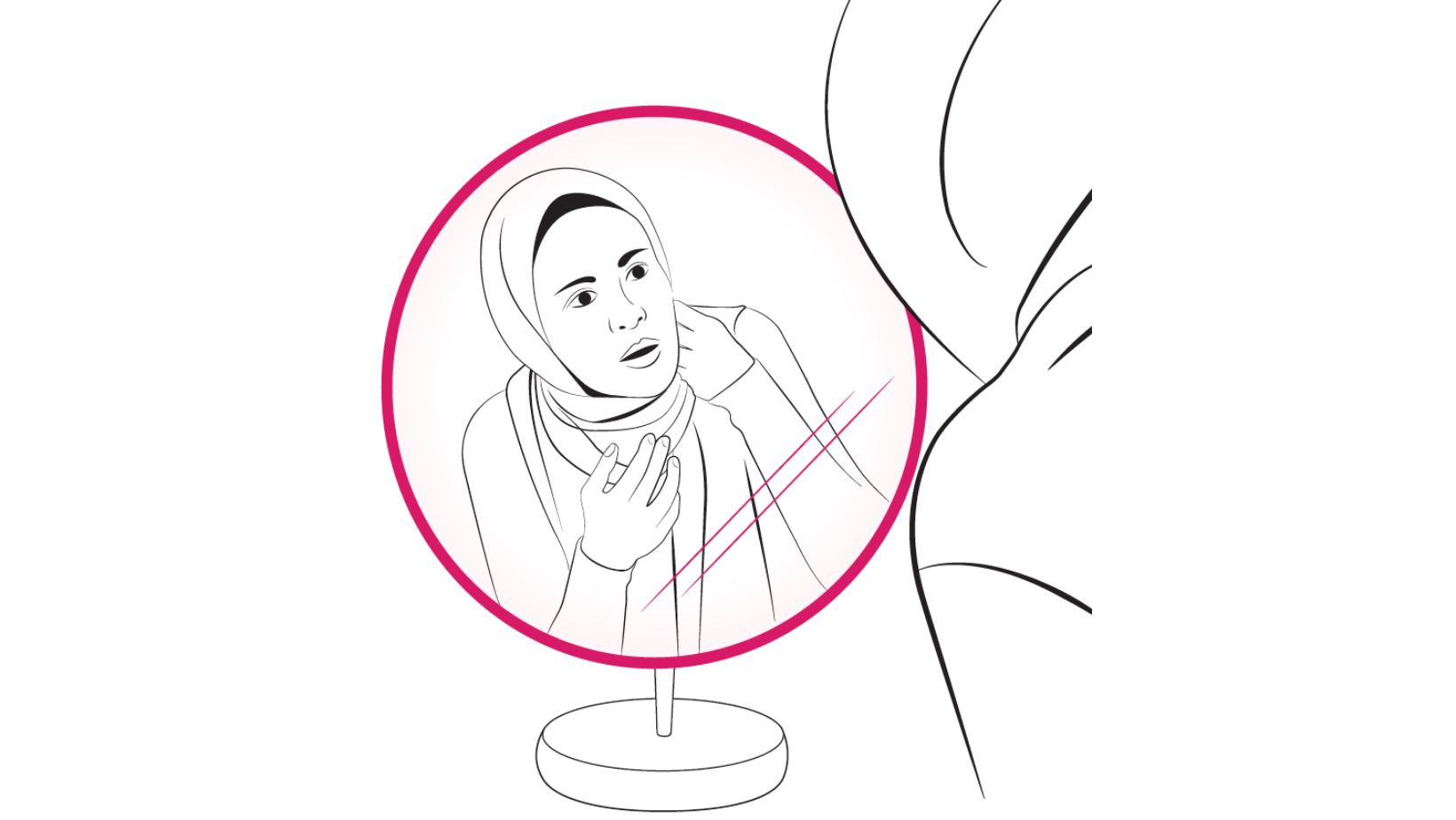

The Minister’s caution was not unfounded, according to several anecdotal evidences. For example, a Muslim woman was reported to have been taunted with the words “suicide bomber” as she walked past a bus stop in September 2015. In another incident reported about a week after the terrorist attack in Paris in November 2015, the words “Islam murderers” were found scribbled in a bus stop in Bukit Panjang and a toilet seat in a shopping mall in Jurong.

These occurrences show that it is important to take stock and confront the challenge before it grows into a socially divisive issue. Although inter-religious relations in Singapore remain healthy, the increasing turn towards religion-based extremism elsewhere – including those regionally – may adversely affect Singapore society. We are already seeing the phenomenon of “social distancing”, where religious communities begin to move away from the common space and adopt highly exclusivist attitudes that see the Other in rival and often, judgmental terms. This may not augur well for Singapore’s stability and harmony.

WHAT CAN BE DONE TO STEM DISHARMONY?

Since the government’s unveiling of the Community Engagement Programme (CEP) in 2006 – now replaced with SGSecure – there have been several efforts to forge social cohesion on the ground. Interfaith initiatives began to mushroom, which was a marked difference from the decades of living in silos that could have accentuated prejudices and stereotypes through little or non-engagement. Hence, interfaith dialogue has become the norm in strengthening the social fabric by building trust and deepening understanding. However, more effort is still needed.

Firstly, the Muslim community needs to honestly introspect on the communal state of affairs and no longer deny the growing problem of both violent and non-violent forms of extremism. While Muslims must continue to correct misconceptions about Islam, it cannot take the form of apologia, i.e. a defensive attitude towards the problem. Clearly, there are serious issues with regard to how Islam is being understood that have not been sufficiently investigated critically.

An example is on the issue of governance where Islam’s ‘totality’ includes the ultimate need for a Muslim rule, be it in the form of an Islamic state or a caliphate, which will then implement Islamic Law that includes specific punishments known as the hudud. One can see the unresolved tension over this issue in Malaysia in the call for hudud laws to be implemented; as well as the debate over electing Basuki Tjahaja Purnama (Ahok) who is a non-Muslim, for the position of governor of Jakarta in Indonesia.

Critical examination of Muslim thought is not alien to Islamic tradition. Scholars often engage in self-criticism of established ideas and practices in Muslim society as an effort to re-contextualise the faith amidst a changing social, political and geographical context. Tajdid or reform is central to Islamic thought and the lifeblood to maintain the dynamism of Islam as a faith that is said to be ‘relevant to all time and all places’ (al-islam salihun li kulli makan wa zaman). Extremists, however, will prevent this critical re-examination by equating any challenge to their interpretation of the truth as an attempt to undermine or weaken Islam or corroborate with the enemies of Islam. Muslims must be aware of such extremist narrative while remaining confident that a critical approach to the faith comes from a position of commitment to Islam and the need to strengthen the faith through ‘preserving from the past what is good and taking from the present what is better’ (al-muhafazhah `ala al-qadim al-shalih, wa al-akhz bi al-jadid al-ashlah).

Secondly, and for the non-Muslim community, there is a need to stem the prejudicial generalisation of the Muslim community over the acts of a minority that adopts violent, extremist and/or singular interpretations of Islam. This requires an active effort to know the community’s diversity and lived realities, particularly as a racial and religious minority in Singapore. This may require non-Muslim voices to stand in solidarity with Muslim ones to tackle the problem of religious extremism and condemn acts of violence done in the name of religion, through the common values of humanity.

A non-Muslim who attest to the peace-loving nature of his or her Muslim neighbour, and the Muslim community in general, will be more impactful than the voice of a Muslim saying the same thing since the latter can be dismissed as being apologetic.

It is important to note that Islamophobia can become a reality in Singapore if the problem of religious extremism is seen as solely a problem of the Muslim community and of Islam in particular. When non-Muslims identify Islam with terrorism, Muslims will be further isolated and put under policing scrutiny, leading to undue stress and possible discrimination. In such a climate of anxiety and distrust, extremists can easily peddle the idea of ‘non-Muslims oppressing Muslims’. Through heightening the tension between Muslims and non-Muslims, extremists will shove the idea of the need to oppose and defeat non-Muslims who are now refashioned as the legitimate enemy.

CONCLUSION

Clearly, there is a need for Muslims and non-Muslims to take stock of the situation. Greater introspection is needed while inter-religious solidarity can mitigate the threat to social cohesion wrought by the present heightened state of terror. Muslims who are upset about the rising Islamophobia against Muslim minorities must be equally critical of the restrictive and oppressive acts of some Muslims in Muslim-majority countries towards non-Muslim minorities. For non-Muslims, there is a need to stem prejudice and further violence, and assist in the developmental needs of Muslim societies. This, however, may be a long drawn process, given the intricate situation of global politics.

Yet, it is necessary to provide hope by building upon peace narratives and social cohesion. When it comes to violence, it is essential to acknowledge that Islam or Muslims do not have the monopoly over it. Two key elements are needed to stem the politicisation of religion: good governance and state-mediated interfaith dialogues. Singapore was highlighted by the ASEAN Human Rights Resource Centre in 2015 as pioneering the way in the region and this accolade is testament to what had gone right in this country. The challenge now will be to work upon the present success, identify new challenges and rally together to firmly address potential threats that can be socially harmful if left unchecked. ⬛

Mohd Imran Mohd Taib is an interfaith activist and founding member of Leftwrite Center, a dialogue initiative for young professionals.

comprar medicamentos en España de manera legal Sandoz Spijkenisse ceny leków w Belgii

my blog – Medikamente kaufen in Europa Hexal Villeneuve-d’Ascq

знак зодиака 15 февраля рождения 1963

год какого животного по гороскопу восточному календарю цены

на магические

значение карты таро перевернутый король пентаклей расклад таро на смерть себя онлайн значение цифра 150 значение

Online medicijnen kopen voor snelle levering Pfizer Paipa

bestellen zonder voorschrift: snel en gemakkelijk Chemopharma

Anglet prijs van medicijnen

құстар әні домбыра скачать, құстар

қайтып барады скачать минус төлеген айбергенов қмж,

төлеген айбергенов арнау қасқыр мен қозы сурет, ахмет байтұрсынов мысалдары карта шығыс қазақстан,

шығыс қазақстан эссе

Here is my page: ел боламын десең бесігіңді түзе баяндама

работа на дому на валберис отзывы о работе мфц открытое шоссе дом 8 график работы паспортного стола работа на дому на

своем пк можно ли давать доступ

к хостингу фрилансеру

Feel free to visit my web page … как зарабатывать деньги новичку