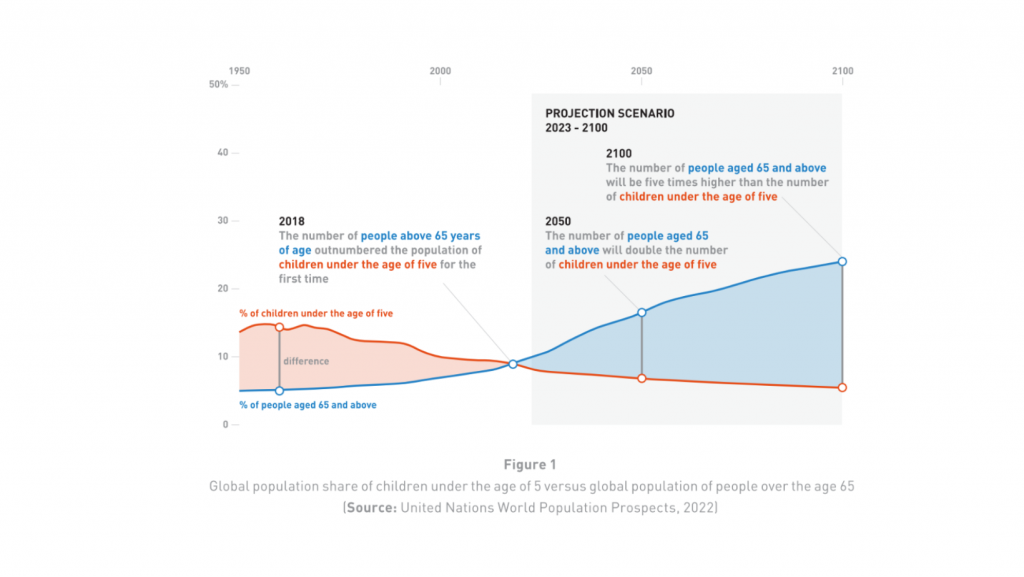

The global population of individuals aged 65 and above is rising worldwide and this trend is largely irreversible (World Social Report, 2023). Individuals are generally living longer due to general improvements in health and survival and with dropping fertility rates, the age dependency ratio is also increasing, thus the inevitable result of the demographic transition towards longer lives and smaller families. This trend is projected to continue, and the world will see increasing proportions of seniors as time progresses. Figure 1 illustrates a crossover diagram depicting the projected changing ratio between seniors and children in the world population.

In 2018, just 6 years ago, the number of seniors aged 65 and above outnumbered children under 5 for the first time. By 2050, seniors aged above 65 will double (2.1 billion) children below 5 years and many of us reading this article today will likely live long enough to watch this unfold and join this statistic. By 2100, perhaps three to four generations down, our descendants will merely see 1 child for every 5 senior persons. The world will look vastly different then and we are sitting right through this historic transition.

This shift in population ageing started in high-income countries but lower and middle-income countries are now also experiencing it. Decreasing fertility rates do, after all, on top of increased life expectancy, influence the ageing of populations, as they do for the shrinking of populations. According to a study by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), the population of 75% of all countries worldwide is projected to shrink by 2050, and at the end of the century, it will shrink by 97%. Only Samoa, Somalia, Tonga, Niger, Chad and Tajikistan are expected to have fertility rates exceeding the replacement level of 2.1 births per female in 2100. It is also interesting to note that by then, when the number of seniors is projected to reach 5 times the number of children below the age of 5, the overall world population is also expected to decrease after hitting approximately 10 billion (World Health Organization).

WHAT DOES THIS MEAN FOR US, RIGHT NOW AND BEYOND?

As quoted by IHME researcher Natalia Bhattacharjee, the “implications are immense”. However, these are predictions after all (albeit informed ones) and the balance between challenges and opportunities should be taken into consideration while processing these figures. There are benefits to having a smaller population, such as for the environment and food security despite disadvantages for labour supply, social security and nationalistic geopolitics. Not all researchers agree either on these projections. For example, the IHME study predicts the global fertility rate to fall below replacement levels around 2030 but the United Nations predicts this by 2050. Despite this, it will happen. Some of us will live to see it, and others won’t.

While this shift is unavoidable as societies progress and evolve, collective actions and policy decisions have the influence to shape its path and consequences. Population ageing also needs to be understood as more than just a set of discrete concerns for a mere group of older individuals. It is set to impact all sectors of society, including labour and financial markets, demand for housing and transportation, and especially family structures and intergenerational ties. Postponing critical measures and being unprepared when a ‘silver tsunami’ arrives will impose high social, economic, fiscal, and health-related costs.

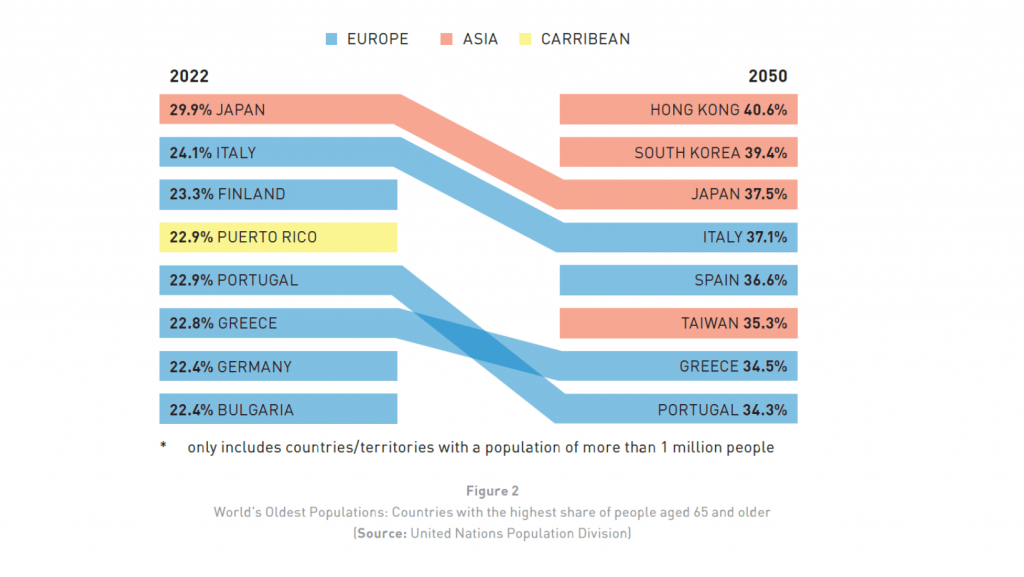

The prominence of seniors in policy-making discussions was underscored in the National Day Rally 2023 speech, which emphasised Singapore’s status as one of Asia’s fastest-aging societies, with the proportion of individuals aged 65 and above rising significantly over the past decade. Asia is also increasingly at the forefront of the ageing trend, with Hong Kong, South Korea and Japan projected to have the highest share of seniors aged 65 and older by 2050 (see Figure 2). Singapore, at 15.12% as of 2022, is projected to reach 36.51%, well over the worldwide projection of 24.03% by 2100 (United Nations World Population Prospects, 2022).

Our community, perhaps thankfully, is not ageing as rapidly. This demographic shift in Singapore is not uniform across all ethnic groups, with Malays, who represent the majority of Muslims in the country, experiencing the ageing process differently, due to larger family structures1. Even so, our fertility rate of 1.83 (as of 2022), still contributes to a steady rise in the community’s old-age dependency ratio2.

The expectation for children to personally care for their elderly parents is strong in the community, rooted in the deeply ingrained value of filial piety. However, with the growing prevalence of dual-income households, singles, and perceived lack in services and programmes, meeting the needs of our seniors will increasingly add pressure on our Muslim caregiving organisations in the long run as our families get smaller. Furthermore, the balancing act between professional commitments and caregiving responsibilities will also strain individuals who remain single or are part of dual-income households, as they contend with limited available time.

Over time, we may need to increasingly address the stigma associated with seeking external assistance and out- sourcing care due to necessity and it should not diminish the importance of familial bonds. Rather, it can even enhance the quality of care provided to the elderly by well-trained and qualified service providers. Caregivers too, need their respite after all.

EMPOWERING SENIORS TO EMBRACE ACTIVE AGEING

Ageism refers to self-limiting beliefs about the physical and mental capacities of seniors. It can also manifest in various ways. It can be institutional, where for example, workplace policies favour the promotion of younger employees as opposed to seniors with extensive industry experience. Interpersonal ageism occurs when a person overcompensates for a senior’s presumed needs, like speaking louder or slower to a senior with intact cognition, followed by comments like “they are sharp for their age.” Self- directed ageism refers to internalised biases wherein seniors believe they should not or cannot pursue certain activities due to their age, for example, wanting to pick up a new hobby but believing that they are too old to learn anything new. Sadly, ageism in all its forms restricts seniors from exercising agency, limiting their rights to independence, values, priorities, and preferences.

A good real-life example of ageism at play is when Lien Foundation first rolled out Gym Tonic, an evidence-based, senior- friendly strength-training programme that improves the functional abilities of the elderly with advanced equipment and software (TODAY, 2015). This is a strength training programme to help seniors restore, maintain, and improve their physical mobility. It faced considerable pushback at first due to ingrained perceptions that strength training is ‘dangerous’ for the elderly. This is despite it having demonstrated otherwise in countries like Japan and Finland.

WHAT IS ACTIVE AGEING?

Active ageing is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as “the process of optimising opportunities for health, participation, and security in order to enhance quality of life as people age.” It focuses on promoting active ageing that covers physical, mental, and social well-being, advocating for active engagement in life, not simply passive acceptance of decline. This active ageing framework consists of three pillars highlighting the importance of social participation, physical health management and security measures in place.

Active ageing is not simply a group of seniors going on walks and participating in Qigong in our neighbourhoods. It provides guidelines in the following areas3:

- Participation: A senior is given opportunities to participate in socioeconomic, cultural and spiritual activities according to one’s capacities, needs and preferences.

- Health: A senior is able to self-manage one’s health and keep risk factors for chronic illnesses low to remain healthy for a longer time.

- Security: Assurance that protection, dignity and care are available if seniors are no longer able to support and protect themselves

Limited understanding of active ageing can lead to underutilised resources and support systems. Worse still, it perpetuates a self-fulfilling prophecy that seniors are incapable of doing much after a certain age, further prioritising dependence on younger generations and resistance to change by individuals both young and old. Going back to the projections in Figure 1, by 2050, and particularly 2100, societies cannot afford to have a large population of able seniors and those younger with self-limiting beliefs of what seniors are capable of. Imagine the strain it will impose.

Even in the event of physical and mental decline, fear of mortality and changing dynamics within a family may significantly impact them emotionally as well and they too deserve to feel secure and supported in comfort and dignity without judgment.

CLOSING WORDS

I think living in Singapore, where the furthest one can be from a loved one is probably an hour’s drive away, it should not be too difficult to maintain close contact with senior family members and encourage them to participate in various community activities. It is unfortunate that despite our close proximity, loneliness among our seniors persists. In time, when our seniors outnumber our youths by a lot, I hope to see our society evolve to one that allows our seniors (and by then, I’ll be one of them) to shine and achieve greater visibility, as well as prominently represented in socio-economic, cultural and spiritual spaces as active contributors instead of passive audiences.

My stepmother lives overseas in a retirement community. She leads a simple yet fulfilling life and despite living apart from her children who are spread across different states, she remains connected through regular phone calls and occasional visits. This does not, however, make her lonely or unhappy. She finds companionship among her fellow neighbours and has access to professional healthcare workers when needed. She is an avid reader and every year, she knits blankets for the homeless in her community, bringing warmth and comfort to those in need through winter. She is a busy senior indeed and it gives her a sense of purpose and fulfilment and she is always cheery when I visit. I hope to follow in her footsteps, when I’m much older, embracing life with passion and purpose, giving back to the community and only limiting myself to what I actually cannot do, instead of what I think or what others think I cannot do. My golden years may just be my best ones yet as my age will not define me, God willing.

1 The Malay community still maintains a relatively youthful age profile compared to the national average. The median age for Malays was 31.4 years, while the national median age was 37.4 years. The proportion of working-age adults (aged 25-64) within the Malay community is currently higher than the national average. 71.5% of the Malay population was in the working age group, compared to 73.7% for the entire population. (Source: Demographic Study on Singapore Malays conducted by AMP)

2 Ratio of older dependants (people older than 64) to the working-age population (those aged 15-64), who will be taking care of their senior parents, for example.

3 Adapted from WHO’s policy framework on active ageing.

Rifhan Noor Miller is Centre Manager for the Centre for Research on Islamic and Malay Affairs (RIMA). Her research interests include gender, equity and social justice issues.