While the Malay community has made significant socioeconomic progress over the last three decades, it continues to grapple with the problem of overrepresentation in the lower rungs of the socioeconomic ladder. At stake is its social mobility.

The problem is compounded by the economic outlook for Singapore, which can be described as the most uncertain in its post-independence history. In his Budget 2017 speech last February, Finance Minister Heng Swee Keat outlined some developments that could pose serious challenges to Singapore’s economy: slowing global trade and investments, which Singapore is highly dependent on; and rapid advances in technology that is disrupting traditional businesses and jobs.

This is not to say though that the future is all gloomy. New opportunities may emerge, which may make available pathways for progress that those from the lower socioeconomic backgrounds could capitalise on. For example, the shifting emphasis from academic qualifications to skills, which threw up possibilities such as Earn and Learn Programmes (ELPs), promises the prospects of acquiring deep skills while drawing an income.

The upside of the future economy notwithstanding, it is imperative that, to adapt and thrive in an economy that is likely to be characterised by disruptions and phenomena such as the gig economy, developments which destabilise employment and thus increased instances of redundancy, more families are often made up of dual income earners.

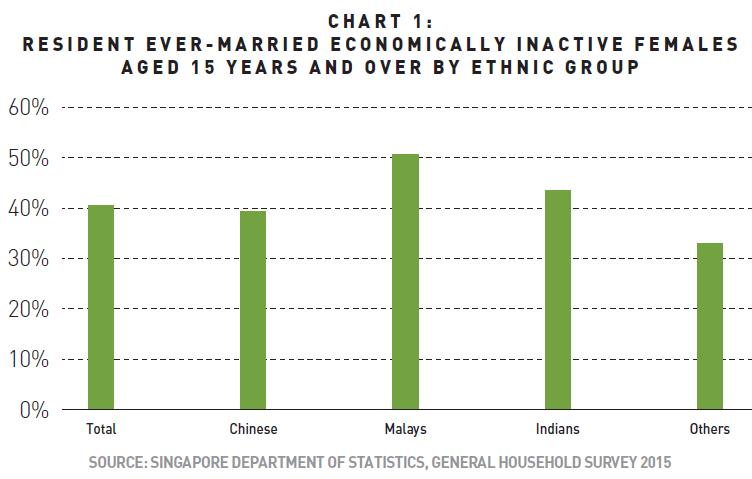

In the Malay community, among females who have been married before and who are currently married, widowed, separated or divorced (ever-married females), 50.4 percent of them are economically inactive, which is defined by the Singapore Department of Statistics as those aged 15 and above who are neither working nor unemployed. The incidence of economic inactivity among ever-married females in the Malay community stands in stark contrast with that of their peers in other communities, as shown in Chart 1.

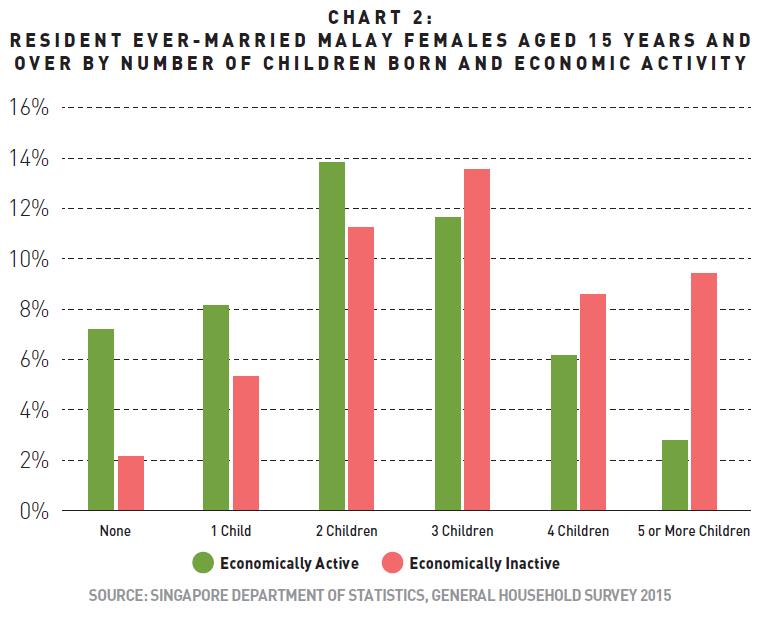

Malay ever-married females who are economically inactive also tend to have more children than those who are economically active, as shown in Chart 2. This statistic poses the question of whether caregiving is a key reason that some Malay women are not seeking employment.

It is also worth noting that, based on the General Household Survey 2015 data, regardless of economic activity, an overwhelming 62.1 percent of ever-married Malay females who have four children or more possess only lower secondary qualifications and below. Given the income that could possibly be earned with lower educational attainments, the perception among the economically inactive from the lower educational category may be that the opportunity cost of forgoing paid employment is not very high. This could be another motivation for not actively seeking employment.

Of particular concern is the economic inactivity among ever-married females in lower-income households.

In 2016, according to the Singapore Department of Statistics’ annual Key Household Income Trends survey, the lowest and second lowest deciles recorded real average household income growths of 1.4 percent and 3.4 percent respectively, down from the 10.7 percent and 8.3 percent that they achieved the previous year.

The government has been responding to the needs of poorer households by rolling out a number of schemes to raise the wages of low-income workers and households. The substantial increase in real wages of the bottom two deciles in 2015 was due in part to ongoing initiatives to raise the wages of low-wage workers. The Progressive Wage Model was introduced in the cleaning, security and landscape sectors. It is hoped that the growth in real wages of poorer employed households could be sustained over a long period as it is crucial for upward social mobility.

Other initiatives to help low-income households include ComCare being tweaked to benefit more families who require short- to medium-term assistance. Among others, the household income cap was raised from $1,500 to $1,900, and the per capita income criterion was reviewed so that families with more dependants could qualify.

There are however still many households struggling to eke out a living and the trends are changing. Ministry of Social and Family Development (MSF) data shows that 5,644 young households, with applicants aged below 35, are receiving ComCare’s short- to medium-term financial aid in the financial year of 2015.

For the Malay/Muslim community, in addition to the array of schemes rolled out by government agencies and community self-help groups targeting low-income families, another initiative to be considered is how economically inactive women among lower-income households could be encouraged to enter the workforce so that there will be more dual income families to tackle job uncertainty and financial constraints.

There is a need to gain a deeper insight into why some women, especially those from low-income households, are opting to remain outside the labour force. According to the Ministry of Manpower’s Labour Force Survey, as at June 2016, among females aged between 25 and 54, 77.7 percent cited family responsibilities as the reason for not working and not looking for a job. 43.7 percent attributed it to housework and 24.5 percent to childcare.

The Centre for Research on Islamic and Malay Affairs (RIMA) conducted a focus group in 2016 involving Malay women from low- to middle-income households to understand their reasons for choosing to not seek employment. The following are some of the key reasons cited:

- The need to attend to their children’s needs is often construed as lack of commitment to their job by employers, thus leading to their decision to leave the workforce.

- Lack of confidence in childcare centres. This could be due to cases of abuse they have heard about or because their children have special needs which they think childcare centres are not equipped to deal with.

- Discouraged due to difficulty in finding employment opportunities that offer flexible work arrangements.

- The need to juggle between caring for elderly parents and young children. Sending the former to an eldercare centre and the latter to a childcare centre are perceived to be a financial challenge.

- Some of the participants are concerned with their children’s education and that their absence could undermine their children’s educational attainments.

It was also found during the discussion that the participants would prefer to work than to remain economically inactive if they are assured that their concerns about their children or their elderly parents would be taken care of.

There are already existing initiatives to incentivise flexible work arrangements (FWAs). Work-Life Grant for FWAs provides funding and incentives for companies to implement structures to accommodate flexible work arrangements so that families can better manage work and family responsibilities.

In addition to this, more could be done to educate employers that workers who have to juggle family needs and work commitments are neither problematic workers nor are they less productive than those with lesser family commitments.

Benefiting from FWAs should not undermine their career prospects or lead to poorer performance evaluation. Rather, striking a balance can make for a more positive view of work.

MSF funds child care centres that run the Integrated Child Care Programme (ICCP), making it possible for children with disabilities between the age of two and six to attend childcare centres with their peers. There is apparently a lack of awareness about such programmes among parents of children with special needs; hence, the need to raise awareness.

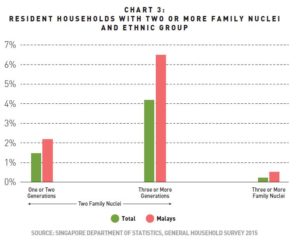

In the Malay community, there is a higher incidence of households with two-family nuclei with three or more generations living together, and three or more family nuclei, compared to the national average, as shown in Chart 3.

Multigenerational families juggling care for elderly and young dependants should be given more help to cope with their situation, by roping in existing eldercare and childcare centres. A better assessment of the needs of such families should be done so that they are aided not only financially but also in terms of facilities for their dependants.

Singaporean societal values, the Malays being no exception, tend to assign to women disproportionate responsibility for caregiving to children, the elderly and disabled family members if any. The decline in women’s labour force participation rate after age 30 is especially telling. For those in the lower income brackets, it would be too costly to delegate such work to paid foreign domestic workers.

In the household, while modern lifestyle has applied some pressure on men to participate more in caregiving, there is still a need to accelerate the mindset shift. Traditional gender roles with regard to caregiving need to be discussed at the community level. National bodies and community self-help groups can perhaps do more to educate men that caregiving is a shared responsibility between spouses.

At the workplace, as noted by sociologist Noeleen Heyzer, former under-secretary-general of the United Nations, and University of Michigan economics professor Linda Lim in their letter to The Straits Times in April 2016, the assumption held by employers, co-workers and government that it is women who will bear caregiving role results in discriminatory treatment in hiring, promotion, training and salaries. This in turn makes it financially rational for families to “choose” to surrender women’s incomes for caregiving purposes. Thus, education initiatives should also be extended to the workplace so as to address factors that keep women out of the workforce. ⬛

Abdul Shariff Aboo Kassim is a Researcher / Projects Coordinator with the Centre for Research on Islamic and Malay Affairs (RIMA), the research subsidiary of AMP.