On my first day at junior college, I was asked by my classmates whether I was an ASEAN scholar. I was secretly pleased, at first, that I appeared to be erudite enough to be mistaken for one. My pride was quickly dashed when they clarified that it was because I did not “sound Malay” when I speak—in other words, not minah enough in the inflections of my spoken English, in my diction and enunciation. On another occasion, while I was out shopping a couple of weeks earlier, a salesgirl hesitantly asked if I was Malay and commented that I did not look like one. The initial look of surprise on her face when I answered her question in Malay was priceless.

These were not isolated incidents. Many a time, people have mistaken me for many other nationalities and races except of being Singaporean and Malay respectively. As hilarious as those situations were, they also aggravated and intrigued me. I found myself questioning my own identity: What does it mean to be Singaporean and Malay, or rather, in favour of the scope of this article, what does it mean to be Malay? What quintessential aspect of ‘Malayness’ was I lacking, despite the fact that official documents categorised me as Malay? My designated Mother Tongue in school was Malay Language (Bahasa Melayu). My family’s way of life is not remarkably different from other Malay families. We speak a mixture of English and Malay at home and school. Our traditional outfit of choice is the baju kurung and the dishes whipped up during special occasions and family events are typical Malay fare of many a Malay food stall. As a Muslim household, we celebrate the festivities of Hari Raya Puasa and Hari Raya Haji as well as observe the religious rulings such as abstaining from pork and alcohol. Though my parents can be considered to be rather conservative, they are also liberal enough to encourage my siblings and I to pursue higher learning. Considering that Singapore has been dubbed the Tuition Nation many times, their emphasis on education buys into the current local mindset. Singaporean-ness aside, why do others not see me as Malay?

In tracing my ethnic genealogy—to know a little more about my family’s history—I found out that my mother is Javanese, or “of Indonesian origin” as per the official books, whereas my father is a mix of Ambon and Boyanese. In addition to this, my paternal grandmother, much to my surprise, is of Pakistani descent. At first I had thought that this whirlpool of genetic mixing is part of the reason why I do not appear distinctively Malay from the common Singaporean perspective. Yet further investigation with friends and relatives showed that this multiplicity is not uncommon to Malays in Singapore. While there may be what can be conceived as a ‘common face’ to Malays as a racial group, no one is just Malay—they are, or are mixes of, Javanese, Boyanese, Bugis, Ambon, and a number of other ethnicities, remnants of a time when the Nusantara was a region thriving in trade and interisland migratory movements. This does not include those whose blood heritage are formed by interracial marriages—between Malays and Chinese, Arabs, and Indians— some of which dated back to pre-colonial trade histories within the region.

It became evident to me that it wasn’t so much of what I lacked or possessed. Rather, the larger perception of Malays is one that posits it as a singular identity in which the various multiplicities that make it is being submerged in favour of a more standardised racial identity. What many perceive to be Malay is rather culturally singular. We have been taught to equate local Malays with Islam. It is true that since Islam was first introduced into the region by Arab traders, it has become so prevalent in most of the Malay cultural practices. In the contemporary Singaporean sensibility, the religion has become so intertwined with Malay culture that it is easy to forget that it actually has Hindu and even Polynesian influences from a much earlier time.

PRICE TO PAY

Growing up, learning about culture was essentially a lesson on uniformity. Schools, the media and even my relatives approached the topic with broad strokes of the brush. The simplification of the Malay identity not only makes for easy categorisation in the official spheres, it also makes society appear efficient and orderly. In some ways, it even presents a kind of united front to the world: “We are Malay and this is our culture”. Thus, simplification can easily lead to collectivity that creates a sense of cultural belonging and identity. This is something that can be observed across the racial spectrum in Singapore. We are familiar with campaigns such as ‘Speak Mandarin’ that omits dialects in favour of Mandarin. This is similar to the submergence of the Malay ethnic groups and the various minor Indian ethnic groups, such as Punjabis being conflated as Indian.

However, what is the price for the stateimposed uniformity and cultural neatness when the reality we live in is actually charmingly chaotic? What do we lose by blinding ourselves to the true diversity of our heritage?

A simple Google check on the history of Singaporean Malays reveals that while indigenous Malays have lived here since the 17th century, it is more than likely that my own Javanese/Boyanese/Ambon ancestors were actually immigrants. In other words, I’m actually not really Malay in the strictest sense of the word. In a way it can be said that:

“I am Malay yet not Malay.”

This is not to say that traces of our rich history do not exist. Our existence in this modern world, where efficiency and neatness is prioritised, is not so bleak as to have been completely whitewashed and diversity eradicated or forgotten. The Javanese headdress that many brides wear with pride on their wedding day, the ever popular nasi padang we savour during lunch, familiar Javanese words such as nyayi in the Malay lexicon, the historical possibility that the production techniques of the Malay songket may have been introduced by Indian or Arab traders. These are more than just well-known symbols of what we claim to be part of the Malay culture. They are living gateways to our true history that have withstood the test of time.

This year, the SG50 celebration is not just a time to celebrate the uniquely Singaporean spirit. I believe it is also a time for contemplation on our own history, both on a personal and national level. In the past 50 years, it seems that the Malay community, in their desire to assimilate into the standardised, westernized Singaporean society, is seeing more of their multifaceted cultural identity slowly dissolving, leading to greater cultural dilution. The ease in which Malays and the larger Singaporean society settle into an easy acceptance of homogeneity and national standardizations comes at the cost of the common narrative, of seeing the Malays as a group without internal varieties. Living in a country that prides itself in being a confluence of cultures, to experience this ironic, systematic, gradual uniformity of culture is rather alarming. Is a state mandated culture still truly our own culture? If the Malay community continues on this trajectory, we risk losing sight of our unique heritage. Worse still, we might even limit our own cultural progress. After all, history has shown that the contemporary Malay culture evolved from adapting traditions from multiple sources—both internal and external.

HARD QUESTIONS

Is a culture still considered to be rich and dynamic when it has been stripped bare? Is it still possible for an efficient and standardised narrative to continue maintaining and creating a collective sense of belonging or will it risk alienating future generations? Are we not already seeing this happening on a wider scale as more and more of the younger Singaporeans express a desire to migrate, partly due to an inability to define and relate to a Singaporean collective?

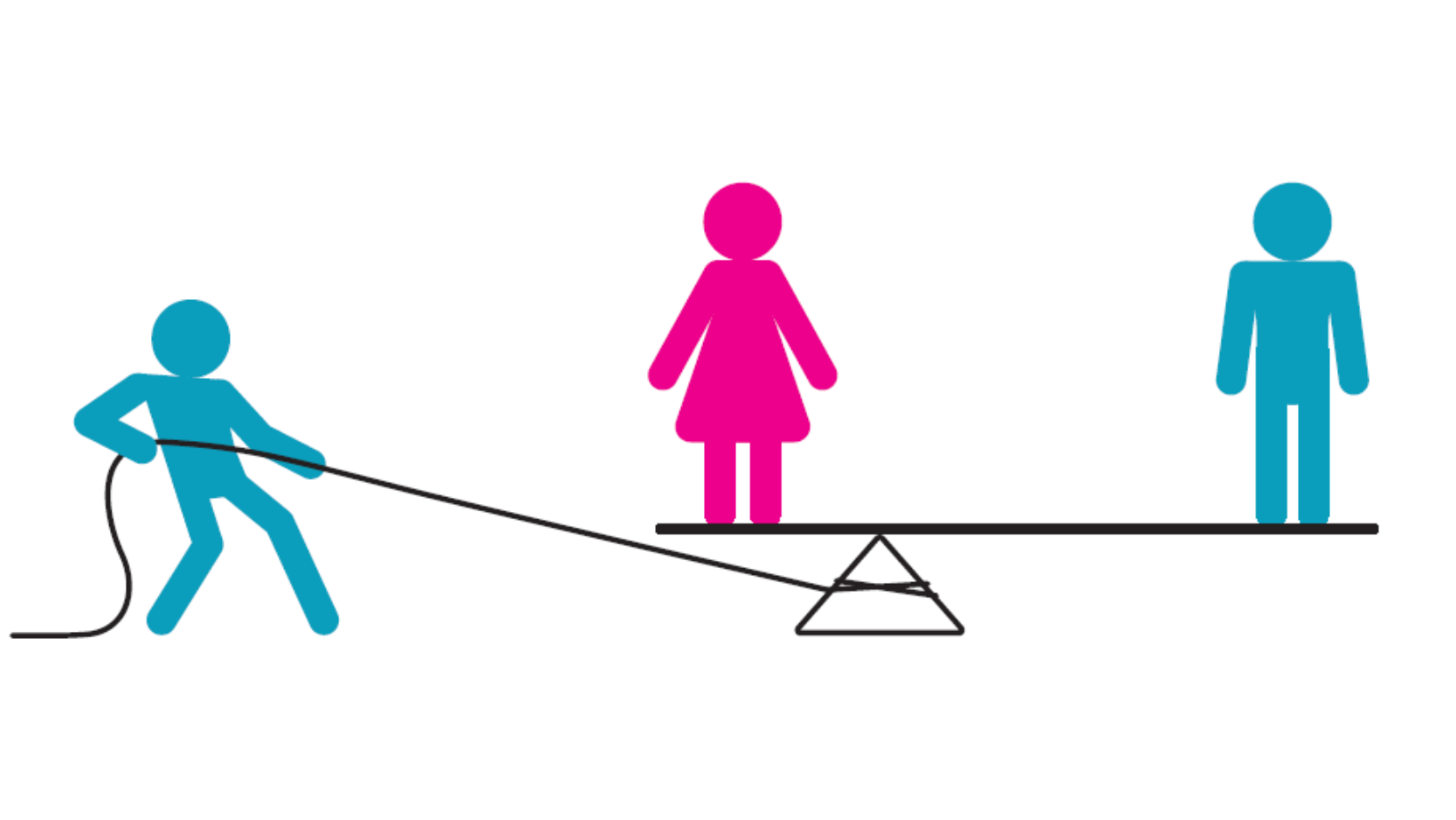

So let us not be too quick to accept simplified, textbook versions of our cultural identity. To shave off our cultural diversity is akin to a cliff being eroded by the waves. Eventually, there will be nothing left. Admittedly, it is no mean feat to balance modernisation while preserving cultural heritage. A compromise must always be made and unfortunately, it is usually the latter that takes the shorter end of the stick. As we continue clinging on to the still existing gateways and artefacts of our true history, let us hope that we have not gone past the point of no return. ⬛

Nur Hamidah Abdul Rahim graduated from Nanyang Technological University with a Bachelor of Arts (with Honours) and a Minor in Creative Writing from Nanyang Technological University (NTU) in 2014. She wrote a collection of short fiction Asian horror for her graduation project and is currently training under the Wild Rice’s Young and W!ld Theatre program. She has starred in a number of productions, including the program’s most recent production, Geylang.

Hi,

I chanced upon this article while reading up on Malay culture. To find out more on Bunga Rampai specifically. Some of your points which I could relate to. For instance the way I sound when talking Malay.

I’m not Malay but it has been my second language throughout my educational journey .

And what I do now ( my business, Auradure Sg) is very much rooted to Malay culture and heritage. I make modern version of Bunga rampai in wax melts form. Enabling it to last longer.

It was nice to have come across your article and I was wondering if you still write . If you do, pls contact me.

Thank you.

Regards,

Naz

Auradure Sg