In 1977, Rosabeth Kanter published her book, Men and Women of the Corporation, introducing the concept of “tokenism” as she covered women’s general negative experiences working ‘non-traditionally female’ jobs and, particularly, their inability to achieve equality in the workplace, despite their capabilities due to their attributed token status, i.e. their low proportion in a workplace dominated by men. Over the years, the term has expanded to also incorporate workplace policies with voluntary or mandated quotas, especially towards minority groups and/or women, in ways that will not change (gender or ethnic) majority-dominated power within an organisation, allowing them mere partial participation. Even so, such practices are, arguably, typically used as ‘proof’ that the organisation does not discriminate against such minorities.

The acknowledgement that tokenism exists allows us to unpack how leadership and representation of minorities are enacted in our everyday professional lives. However, for minority individuals who got to the top through their own merits, an unhealthy obsession over any minority leaders being mere token representatives serves to instead, discredit their capabilities to lead. Disgruntled voices spread like wildfire in our current world of inter-connectedness and on platforms where anyone can post biased and poorly informed opinions as ‘truth’ such as social media, it is so easy to create and grow negativity bandwagons to question an individual’s legitimacy to leadership as token representation, despite attaining the position through merit.

TOKENISM VERSUS AFFIRMATIVE ACTION

Tokenism refers to policies or practices of making only a symbolic effort to include participation by individuals from under-represented groups to give the appearance of equality or inclusivity. Affirmative action, on the other hand, refers to policies designed to redress inequalities created by historical legacies e.g. group discrimination and disadvantage experienced by under-represented groups.

When Mdm Halimah Yacob was sworn in as the 8th president of Singapore on 14 September 2017, she was Singapore’s first Malay president in 47 years, and the first woman president in the country’s history. She also joined the list of other Muslim-female heads of state worldwide like Benazir Bhutto of Pakistan, Khaleda Zia and Sheikh Hasina of Bangladesh, Tansu Çiller of Turkey, Mame Madior Boye and Aminata Touré of Senegal, Megawati Sukarnoputri of Indonesia, Roza Otunbayeva of Kyrgyzstan, Atifete Jahjaga and Vjosa Osmani of Kosovo, Cissé Mariam Kaïdama Sidibé of Mali, Sibel Siber of Northern Cyprus, Ameenah Gurib-Fakim of Mauritius, Samia Suluhu of Tanzania, and Najla Bouden of Tunisia. From the list above, most are Muslim-majority countries.

Singaporeans then did, however, and understandably, have mixed feelings as they couldn’t exercise their right to vote for the winning candidate who would go on to play the largely ceremonial role. Even so, she handled the criticisms with grace and calmly told reporters outside the Elections Department on 11 September 2017, “I promise to do the best that I can to serve the people of Singapore, and that doesn’t change whether there is an election or no election…my passion and commitment to serve the people of Singapore remains the same.”

Mdm Halimah was a strong advocate for social issues long before she was elected and championed various social causes, from mental health issues to help for disadvantaged groups. During her term, she continued to support charities and initiatives for various groups, and she leaves the unique legacy of having steered the country through COVID-19, a global pandemic that led to more than 1.8 million official deaths globally by the end of 2020 alone (World Health Organization), giving her assent to the government to draw on past reserves for COVID-19 public health expenditure.

She also spoke up on behalf of Singapore Muslims amid announcements by the Internal Security Department (ISD) regarding the detention of self-radicalised youths, asserting that their aspirations neither represent Islam, nor the Singapore Muslim community at the interfaith group, Roses of Peace’s 10th anniversary celebration in 2023. She spoke up in encouragement of the Malay community’s significant progress in education and household income in 2023 when much public discourse persists in highlighting achievement gaps between the community and the national average. She also spoke up in support of the White Paper on Singapore Women’s Development in 2022 as well as increasing participation by women in the economy and leadership positions at the Women’s Forum Asia in 2019.

The point here is, it has become clear, 6 years on, that using the term ‘token’ in the same line as her name when she became President is grossly unfair.

Furthermore, representation matters and it matters further that a Muslim and a female is the one championing the causes of her own community. For me, seeing a fellow Muslim female in a headscarf, in a position of power who remained focused on her responsibilities and delivered despite initial raised eyebrows is something I am proud of as a fellow Muslim woman. Beyond Singapore, let’s also not forget that much of the secular world views Islam as an intolerant religion that oppresses women, and it is always refreshing to see strong female Muslim leaders holding their ground in a political sea of men.

WHEN YOU THINK YOU’RE ‘ONE OF THE GUYS’ AND ‘NOT LIKE OTHER GIRLS’

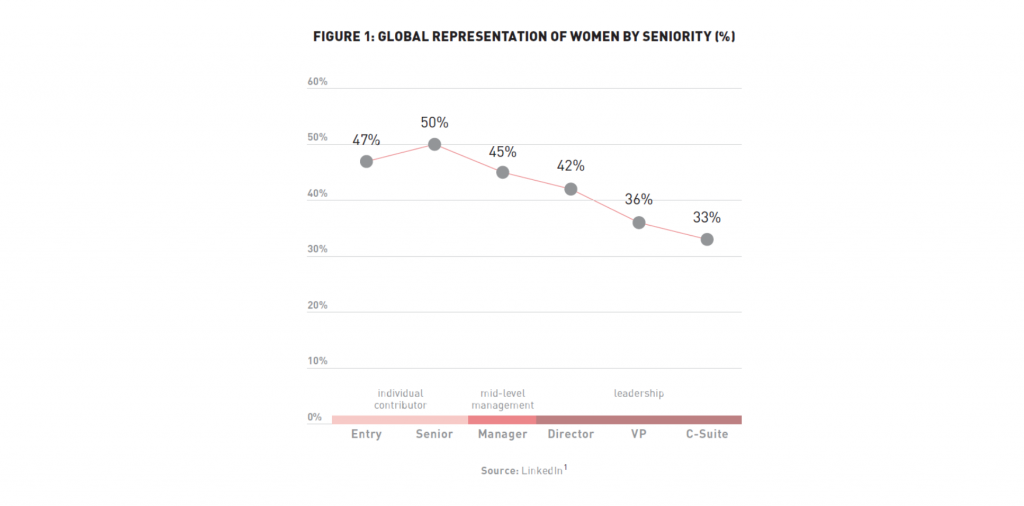

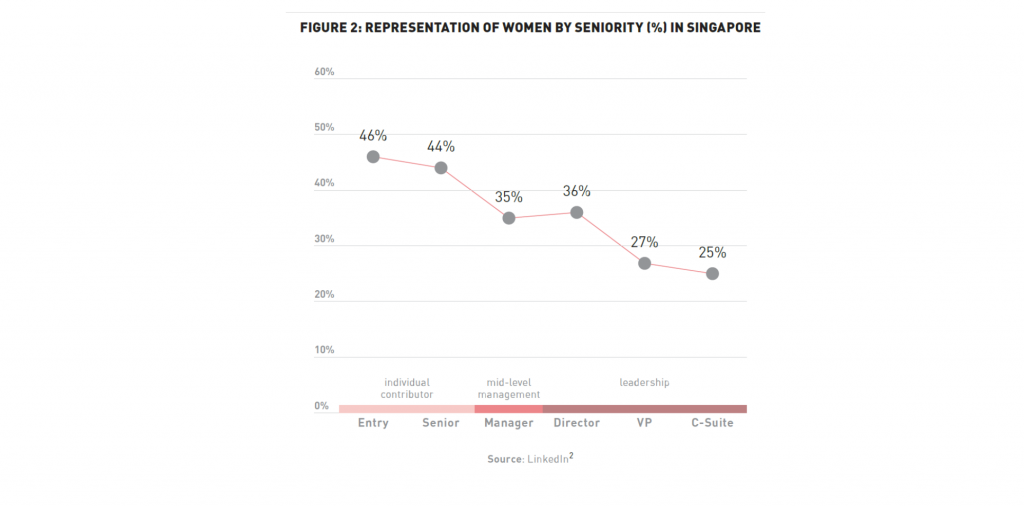

Beyond Singapore politics and politics in general, the percentage of women in leadership positions has only risen slowly and the statistical representation of women in top management and executive positions continues to change at a very emancipation and access to education among women worldwide. Women generally enter the workforce in almost equal proportion to men but the share of women in managerial and leadership positions progressively drops higher up the seniority ladder (see Figures 1 and 2).

In other words, it gets increasingly lonely for women higher up the seniority ladder. This has multiple implications but most importantly, this signifies an increasing under-investment in social capital. Social capital that is usually built through socialising with colleagues and building professional networks. This is made especially difficult when as a gender minority, the influential networks are made up of mostly men who partake in more ‘masculine’ activities or topics of conversation and you face the awkwardness of being the only woman in a boardroom. In addition, as Muslim women trying to make it in more secular workplace settings, there may be activities that may not necessarily align with their faith, like a working lunch at the team’s favourite non-halal restaurant. These may seem trivial but present real, practical challenges to women. In addition to this, working mothers are even more pressed to juggle work and family.

In a study conducted in the United States (Hewlett, 2002), it was found that 33% of women with successful careers (in reference to business executives, doctors, lawyers, academics, etc.) in the 41 to 55 age bracket are childless and that figure rises to 42% in corporate America. Yet, most of these women yearn for children but were unsuccessful in conceiving later on as they had crowded out the possibility of having children in their earlier years meeting the brutal demands of their ambitious careers. High-achieving men, on the other hand, do not experience such a difficult trade-off. 79% of the men surveyed reported wanting children and 75% have them. I suspect this trend is close to the realities in other communities too, including our own.

Having said this though, I am not proposing a gender war but rather I am looking inward into what it means to be an educated and career-focused Muslim woman of today, navigating male-dominated professional hierarchies without downplaying my femininity, to be taken more seriously. Beyond my community, to be accepted in more secular professional circles which may or may not have formed opinions on the rights of Muslim women from biased reporting without downplaying my faith. Unfortunately, internalised misogyny is also present within us women, and as mentioned above, it is already increasingly lonely for women striving to reach the top of their careers. It is especially lonelier to be judged by other women with varying ideas of what it means to be a woman and a good Muslim woman on top of it.

TEAM MUSLIMAH

At the end of the day, we are all trying to be the best versions of ourselves regardless of what our aspirations may be, and we can indeed be kinder to ourselves as well as our peers from a place of compassion and female camaraderie. By the time this piece is published, Mdm Halimah would have already stepped down and I will miss seeing her portrait around our institutions, what it represents and proudly proclaiming to my non-Muslim family members overseas that we have a Muslim woman in power so no, we Muslim women are not oppressed. As a headscarf-wearing Muslim woman, I also want meaningful representation, not tokenism. Perhaps, sometime soon, we will again have another Malay elected head of state whom the public voted for, and we can finally burn that token to the ground.

1 LinkedIn. “Gender Equity in the Workplace.” LinkedIn, linkedin.github.io/gender-equity-2022/. Accessed 29 Sept. 2023.

Rifhan Noor Miller is Centre Manager for the Centre for Research on Islamic and Malay Affairs (RIMA). Her research interests include gender, equity and social justice issues.